HGLA #110 - Don't look; don't see

Our compliance in the art of omission

Final flights

Of clouds

I’ll never see again

Lost like me

Stretching for more

Fading away

I want so much

But they won’t listen.

They can’t.

Flowers underfoot.

Maybe now

they’ll hear.

I never know where to look.

Under the sheets.

Under the lies.

I don’t even know

if I want to see anymore.

See what I know.

What I know I don’t want to hear.

What I’ve been avoiding.

We’ve concealed enough.

Learned misinformation.

An agreed code.

Neither of us will look.

Neither will see.

Just different people

on separate quests,

learning how to be one,

learning how to be ourselves.

But something is breaking.

I had to do it.

I couldn’t go any other way.

The steps I had to take.

A moment of weakness.

A moment of pain.

I say I see,

and we both realise I can’t.

Unsay it.

Unsee it.

It lies in the open.

Pandora is free.

We hid it for so long.

Pretended it didn’t happen.

It wasn’t happening,

but it was.

We knew,

and we wanted it to be something else.

We still do.

But looking has its own problems.

Seeing, for one.

Will it free me up,

help me heal,

or does the tissue have to split

before I can see what’s real.

At least I was comfortable,

knowing what I didn’t.

A space held open.

A space unconfirmed.

No clouds anymore.

Just rain on the ground.

I wish I knew where I was going.

Schrödinger’s cat,

half full in my head,

executed by opening,

with flowers underfoot.

Fog of War

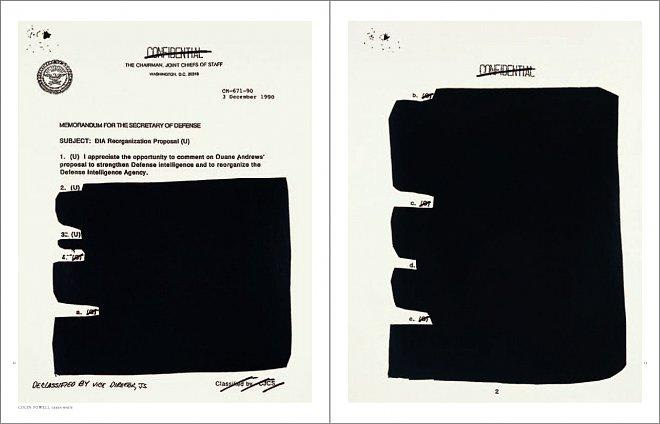

Much is hidden in life, most of it by what we do not see.

The fog of war is real, and we experience it day to day, but treating it like weather is a mistake we often make. The fog around us has bias. It has direction.

In the 1800s, Clausewitz wrote On War, and it is still relevant today. He wrote: “Everything is very simple in war, but the simplest thing is difficult.”

Conflicts show us reality. War is humanity operating at its extremes, and when we look at the way we navigate these extreme conditions, we often reveal how many operate day to day.

“Many intelligence reports in war are contradictory, even more are false, and most are uncertain.”

War and Mondays are not that different. Partial data, expensive ways to find truth, and severe consequences for being wrong.

So how do we see clearly in a perpetually uncertain world. We observe the fog. The most important things are rarely hidden by accident. Hiding things costs time, it costs money, and the tools used to hide them often reveal the actors at play.

Georg Simmel is a sociologist interested in secrecy. He writes that secrecy is a universal sociological form, and it has nothing to do with the moral valuations of its contents. He sees secrecy as a tool.

It is a way to regulate who belongs, by defining those who know and those who cannot. The formation of a boundary allows status to form. Loyalty occurs because people are allowed to know.

“I know something that you don’t know.”

A childlike line that shows how early on in our social development we understand that controlled disclosure allows prestige through proximity. Being in the know becomes a way to show that we are part of a pack.

But for those that grant access, it gives them a leash to pull. It gives them a position within the pack that establishes a natural hierarchy. And most importantly a fog to play with.

At first it is relatively un-nuanced, but as we learn the power of secrecy, it becomes clear that a counter-intuitive way of navigating the world, well-resourced and understood by the few, becomes a great way to control the many.

When we look at control generally, we think about lies and the pushing of media narratives, but the easiest way to create control is to provide a menu of options that, instead of defining what one must not do, creates a narrative of discourse between two lesser options.

“The press may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about.”

Bernard Cohen

A menu is created, and we spend our time debating which part is best. The conversation slips into something more shallow, irrelevant to the real problem.

We live in a world where algorithms and machines are defining the menu. Some may think they left Instagram and TikTok due to their toxic nature and fled to Substack or journals, but the narrative is the same.

An algorithm is about to control how we perform, the content we create, the things we consume. It does not have to do it with every story, but one in six, one in seven, one in twelve is enough to create the idea in our minds that this is what we should be talking about.

I spent a long time researching, teaching, and operating within counterinsurgency (COIN) doctrine (how to do stuff). I love the way militaries share how they approach counterinsurgency, because a lot of what they understand in application of force abroad is what they are already doing at home.

FM 3-24 (US Army field manual on COIN) states that legitimacy is the main objective, and that all governments rule through a combination of consent and coercion. Often these take the form of explicit actions that affect the cognitive dimension.

AJP-10.1 (NATO Doctrine) defines the cognitive dimension as perceptions, beliefs, decisions, and behaviors, and further states that the cognitive dimension is the decisive dimension to achieve an enduring outcome.

Attention has always been the strategy. The fog of war has always been real. Those who seek to define the narrow window with which we view reality will always exist.

But in our current world, understanding what we cannot see is often the most important way of understanding what reality could be, and the space that may exist for us to live a better life.

We might read this and think: so what. It all sucks. But knowing there is a game at play may give just enough of a glimpse to notice that when opportunities are presented, and the feeling of freedom and choice is provided, maybe the right question is not which one, but what else.

That may not provide something tangible in that moment, but that small moment of freedom is enough to build something out of, or at the very least see, what we have been ignoring for some time.

Work

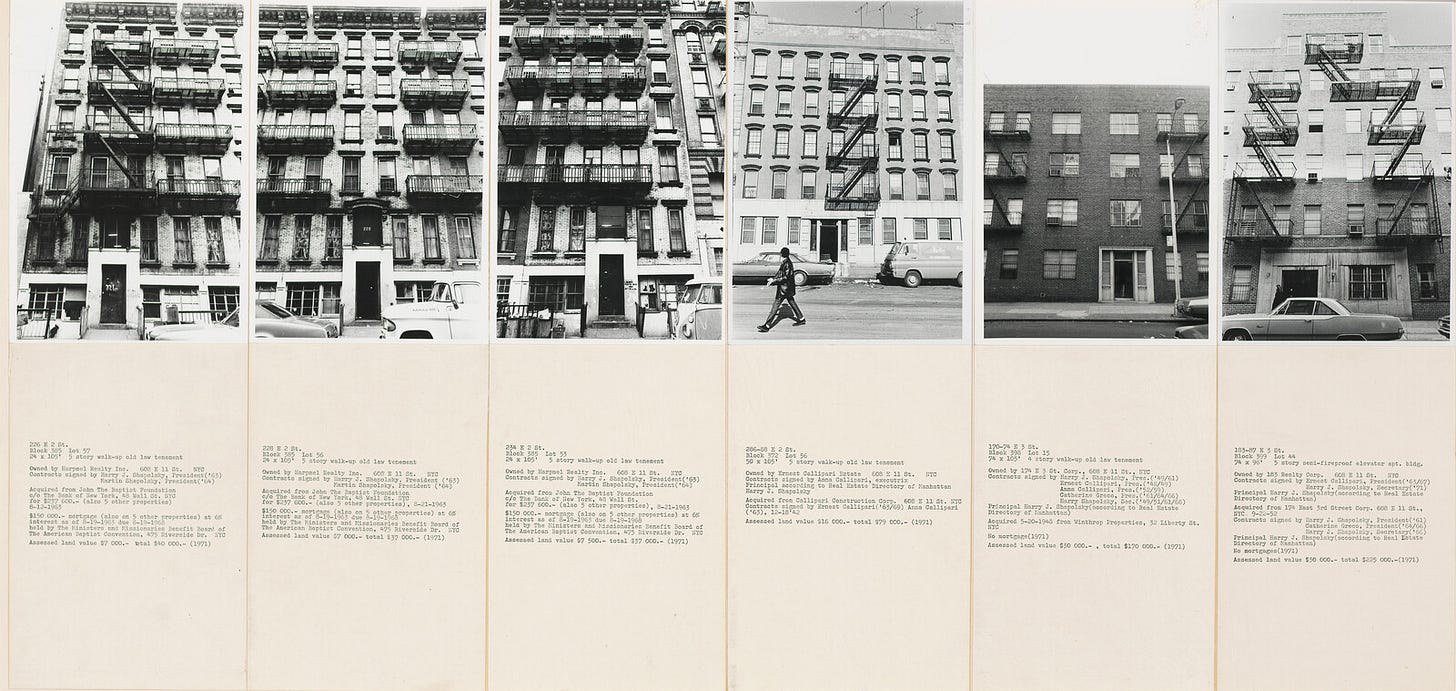

I’ve just installed this in East Village.

It’s a giant metal box, and you draw on it.

Over the last few years, I’ve been very inspired by Sol LeWitt and Rudolf Stingel.

I love the idea that creativity comes from exploration within given boundaries, and that limitations, when set correctly, create the space for art.

On the surface, it is cringe.

How else do you convince the public and a real estate developer to let you do this.

The pens are chained to the structure.

There’s a hard limit on where each pen, each colour, can reach.

And inside that, there’s only so much room to write.

Over time, a pattern may emerge.

A pattern shaped by the boundaries built into the system.

And the only thing we’ll really be able to read, in the end,

is the texture of what’s been written.

If you’re on that side of town, have a look.

I like it.

It’s relevant to what I’m saying above.

It’s up for four weeks, open 24/7.

Studio

I’m moving space.

Space is something I’m grateful for.

Space to work.

Space to explore.

Space to find a voice.

I’m grateful for this space.

For the space to show my work.

For the space to know it may not be perfect.

For the space to see what could work.

London has been amazing over the last two years.

I moved back here after everything fell to pieces.

I was mixing my work and my life,

and had to walk away from

what I’d spent three years building in both,

So I could build it correctly.

That has been tough.

I’m in the studio every day.

It’s a rule I seldom break.

The luxury of time

isn’t something I want to remember

having squandered.

Space too.

The King’s Road studio has been incredible to me.

Since opening it up to visits last year,

over 60 of you have been here.

Every visit I learn something new.

About your world.

About my own.

I remember the first visit clearly.

An old friend brought me a bonsai tree.

Daphne.

Back then, I had an easel,

a table for paints,

and two seats from a race car.

I set myself a challenge:

I wouldn’t buy anything to improve the studio

unless I needed it to fix a real problem,

And I’d sold enough to pay for it.

Two years later,

I’ve solved a lot of problems.

I’ve got a lot of stuff.

But I have the same easel,

and I have the same paints.

I’m not sure where the next studio will be,

but I’m going to open it up a little more.

If there is a role the visual artist plays in the creative world,

it is simple.

We look for the right questions and

create spaces that allow them to be discussed.

Musicians paint time.

We create space.

The collaborations and conversations I’ve had

have reassured me that I’m not crazy.

Rarely are the most valuable things to come out of a visit

some contrived conversation about process and aesthetics.

It’s the musings that follow afterwards.

The shared interests.

The books you leave behind.

And, for those that have been here,

the notes you take with you.

I’ve got some friends joining the journey,

helping me document the next few months.

They will be tough.

That is the path.

But I hope I come out alive.

So neither of us ever forget

that whatever it is you want to do

is wholly within your ability.

I believe in you.

Poets Corner

I

The cathedral is sinking!

I ascend

by the sight of it

alone

at six ay em in January.

- Thomas MayFinal words

Continuing perception for two more weeks

Then I’ll be showing you my new space

and mission

Looking forward to going on this journey with you all

love you loads,

- r

x