Notes on Sol Lewitt

Things I've learned from looking at the older kids

I didn’t go to art school.

I don’t know what they do there.

But I did go to a decent business school and, before that, a really good war school, and all I did there was learn what the best entrepreneurs and generals did well (and badly).

So maybe looking at what the older kids do isn’t such a bad strategy for improving.

I’ve had two extremely difficult moments in my art career.

Cash ran out. I lacked direction. Everything went dark.

The path was the same both times. Panic, reach out to friends and family, write letters, fire sale on paintings.

At the bottom of this slope, with nothing left in the tank or the studio, I’m left with one option.

Learning stuff.

The public library has been rescuing me since I was 7. My mum used to leave me there after school and on weekends with some sandwiches and strict instructions not to take sweets from strangers. I’d spend my days with books. I liked them. They felt like home. The internet joined later and did the same thing.

This is a new series where I share that side of my life. The people, books, and ideas that I love. The ones that inspire me. Nourish me. And the ones that keep me going and thinking late into the night.

This week, my notes on Sol LeWitt, an interesting character from the US. I really enjoyed seeing how he formalised making art through other people. When I first came across his work 10 years ago, I wasn’t convinced, but then I watched an interview with an artist in 2009 who was creating his works from the original instructions, and it all sort of clicked. (video at end)

Enjoy.

Sol LeWitt

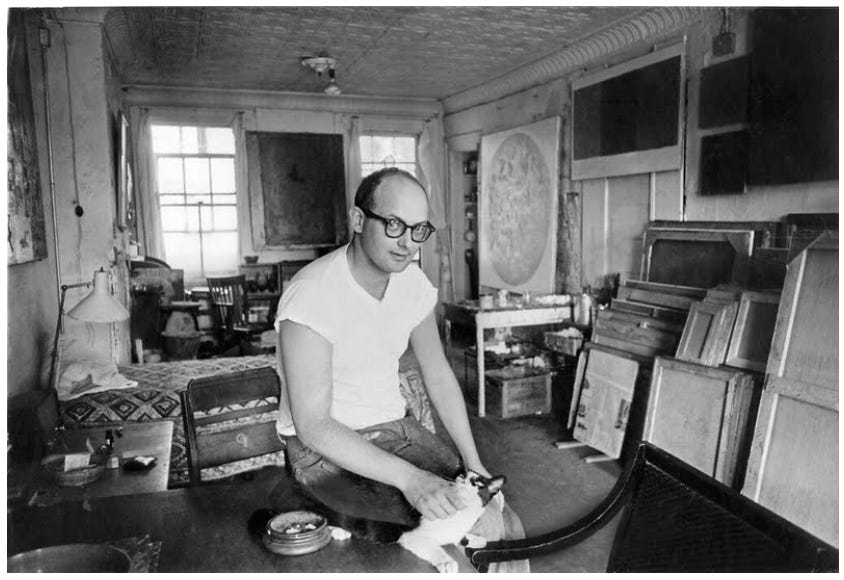

Sol was born in 1928 in Hartford, Connecticut to Russian Jewish immigrants. His dad was a doctor and inventor and died when he was six.

Six years old is a tough age to experience loss. He moved in with his mum and an aunt while drawing on wrapping paper from his aunt’s grocery store, and his mother took him to art classes at the local museum.

Sol studied at Syracuse with a BFA in 1949, and then got drafted into the Korean War (1950). He made recruitment posters in Japan and began collecting art. It’s the start of a collection he’d build for decades, buying work from peers and younger artists. Supporting people with his wallet before he had any real money.

Sol moved to New York in 1953. Studied illustration. Worked at Seventeen Magazine doing paste-ups and mechanicals, and then worked as a graphic designer for I.M. Pei, a Chinese-American modernist architect.

I always find it interesting how artists’ day jobs and history influence their practice. Architects don’t lay bricks; they draw a plan and hand it to builders. LeWitt spent two years watching someone design buildings he’d never physically construct. Maybe he realized that the blueprint is the work and the execution is a job for someone else.

MoMA

In 1960, he got a job working nights at the Museum of Modern Art’s book counter. His co-workers were Robert Ryman, Dan Flavin, and Robert Mangold. It’s pretty incredible that these four artists found each other working the night shift at a museum. They all saw that Abstract Expressionism was exhausting itself, and were all looking for the next thing

At the time, Sol was painting in an abstract expressionist style during the day, and it wasn’t working. He finds a copy of Eadweard Muybridge’s serial photography. Bodies in motion, captured in sequence. Repetition as structure. Variation within a system. I’m not sure if this is what switched him into a deeper systematic approach, but it’s definitely relevant.

Timeline

1928 - Born

1961–62 (Age 34) — Paintings with Muybridge figures. Then puts out Wall Structure, Blue (1962), his first real move toward simplification. No narrative. Colour, shape, texture.

1964 (36) — First group show. Curated by Dan Flavin.

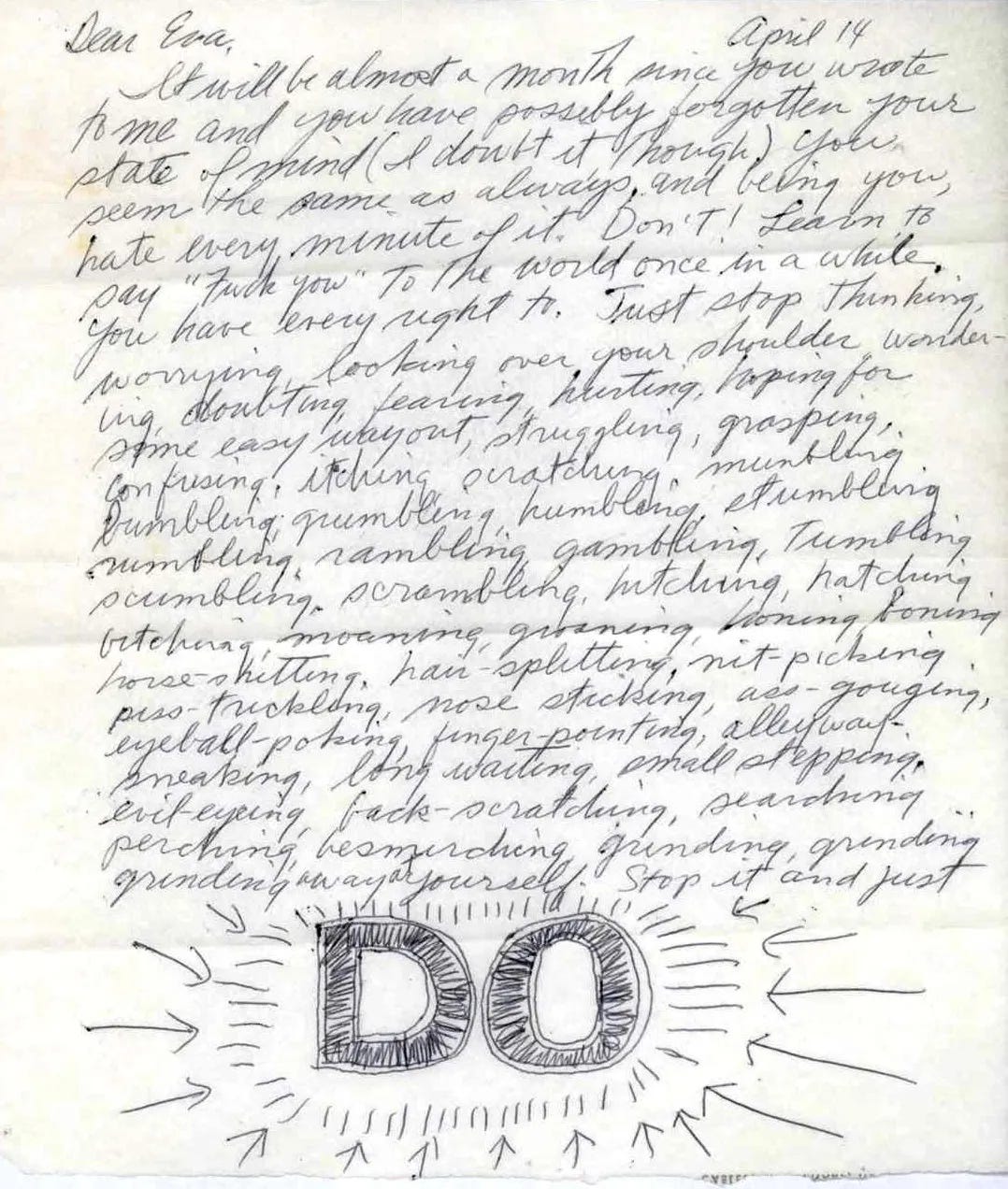

1965 (37) — First solo show at Dan Graham’s ‘John Daniels Gallery’. Open structures, skeletal wooden forms. Also writes the Eva Hesse letter.

1966 (38)— Shows in Primary Structures at the Jewish Museum. The exhibition that defined Minimalism. LeWitt submits an open modular cube of nine units. The cube becomes an ongoing idea.

1967 (39) — Publishes Paragraphs on Conceptual Art in Artforum. This is the text that names the movement. One sentence in particular: “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” He includes one of Eva Hesse’s hand-drawn circles as an illustration.

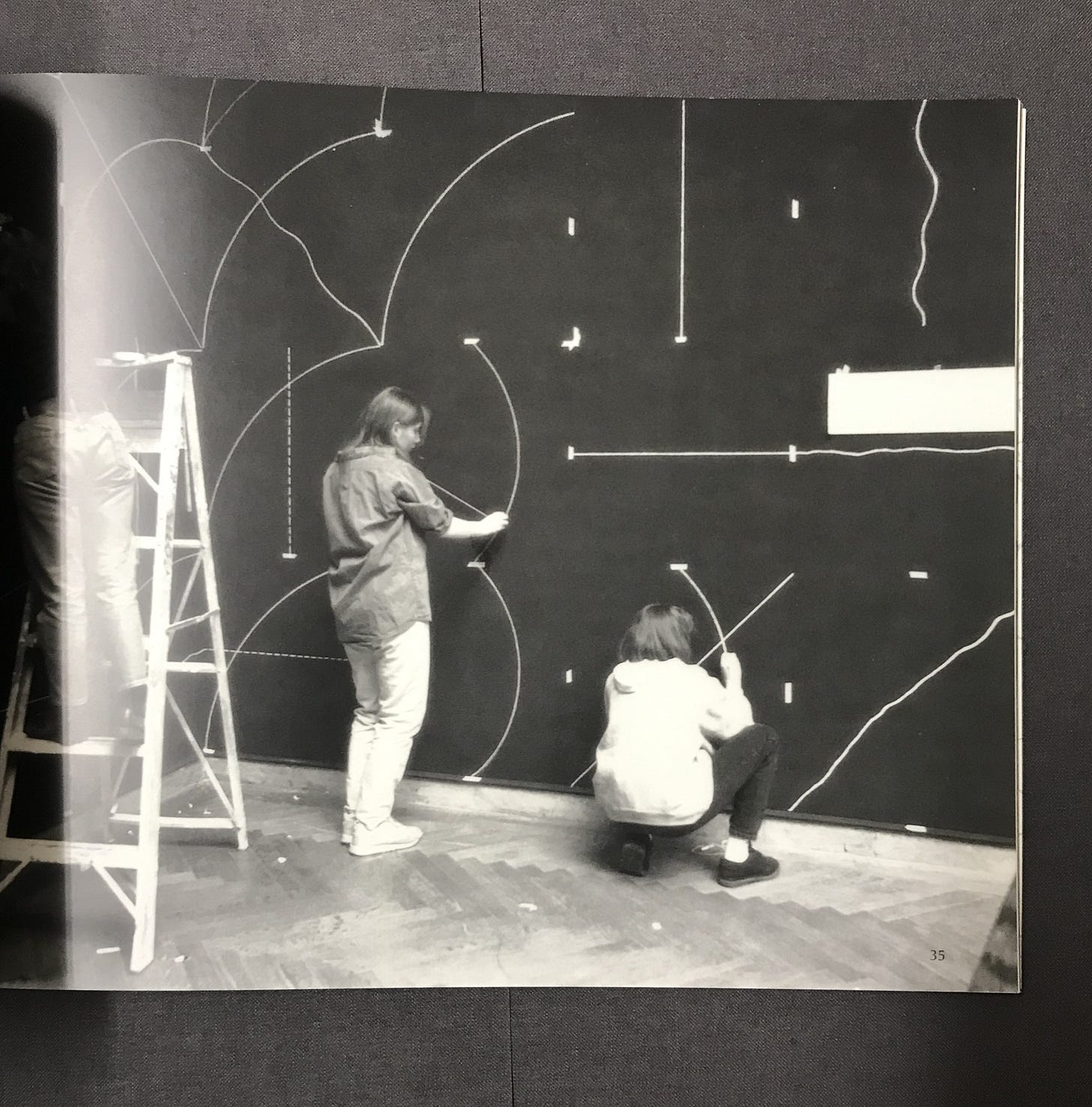

1968 (40) — First wall drawing. Paula Cooper Gallery’s inaugural show. Lines drawn in pencil directly on the wall. The instructions are the artwork. The drawing is temporary. Over 1,200 wall drawings follow.

1969 (41) — Publishes Sentences on Conceptual Art. 35 principles. Shows in Harald Szeemann’s When Attitude Becomes Form at Kunsthalle Bern.

1970 (42) — First retrospective at the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague. He’s 42. Eva Hesse dies of brain cancer. Days later, he creates Wall Drawing #46, uses freehand, irregular lines. raw. A big shift in style, same process underneath it.

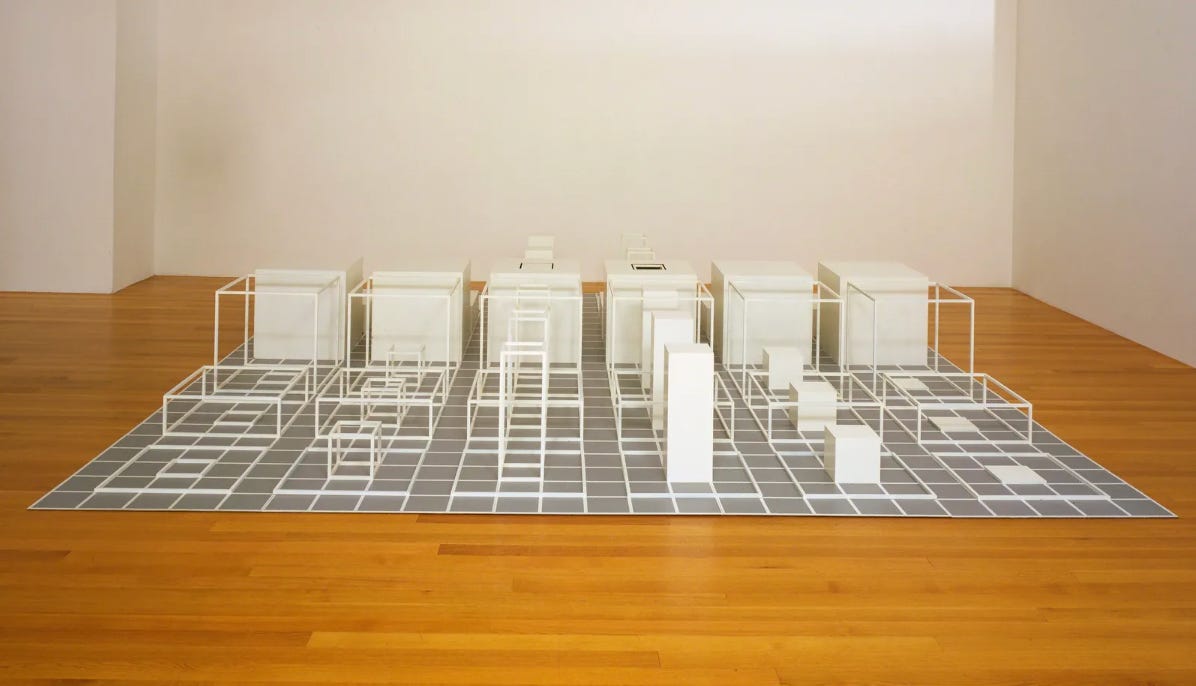

1974 (46) — Incomplete Open Cubes. 122 variations of ways to not make a cube. One of his most recognisable works.

1976 (48) — Co-founds Printed Matter with Lucy Lippard. Artists’ books. Affordable multiples. Getting art into people’s hands without the gallery as gatekeeper.

1978 — MoMA retrospective. He’s 50.

1980 (52) — Leaves New York for Spoleto, Italy.

1982 (54) — Marries Carol Androccio. She opens a wine bar in town. He walks to his studio along a Roman aqueduct every morning.

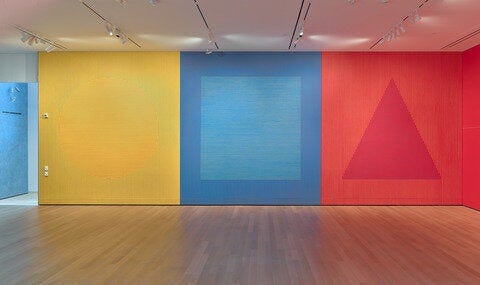

1983 (55) — Big changes. Starts using Indian ink and colour washes. The black-and-white conceptualist becomes a colourist. He’s been looking at Giotto, Masaccio, Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca, frescoes in churches and convents all over Umbria. Begins to try to make work he wouldn’t be ashamed to show Giotto.

Late 1980s — Returns to the US. Settles in Chester, Connecticut. Co-designs his synagogue. Becomes an invisible local legend.

2000 — Major retrospective. SFMOMA, MCA Chicago, the Whitney. He’s 72 and the work is the most colourful and alive it’s ever been.

2005 (75) — Starts the “scribble” wall drawings. Graphite at six different densities. After decades of increasing complexity, he circles back to something almost primal.

2007 — Dies April 8th. Cancer. Aged 78. Just organised a retrospective at Oberlin.

2008 — Sol LeWitt: A Wall Drawing Retrospective opens at MASS MoCA. 27,000 square feet. Three stories. It stays on view until 2033. Twenty-five years of a dead artist’s work being perpetually recreated by living hands.

Evolution

From 1962 to 2007, Sol continued to iterate on the same idea: building a system, defining its constraints, then letting the system generate outcomes he couldn’t fully predict. The cube permutations do it. The wall drawing instructions do it. The colour washes do it. The scribble drawings do it.

What changes is what the machinery processes and creates.

In the 60s, it’s geometry and seriality. In the 70s, it’s language and instruction. In the 80s, its colour and Italian light. In the 2000s, its density and the human hand.

But the question stays the same: what happens when you set up a structure and then get out of its way?

I’ve been thinking a lot about this with the interactive work I do, most recently with the Reflections I. I design prompts. I chain pens. I control the participant. But once it’s in the street, the system runs itself. I don’t interfere. What people write isn’t my art. What they write because of the constraints I build, that’s my art. Sol was doing this for fifty years before I even thought about it.

Italy

In 1980, as one of the most important living artists, he walks away from New York. He’s 52. He’s had a MoMA retrospective. He’s at the peak of the art world. And decides to move to a medieval hill town in Umbria with a population of about 38,000 people.

His house was a small tower on a hillside with a separate studio in the old town. The walk between them crossed a Roman aqueduct - the Ponte delle Torri. He’d been introduced to Spoleto by his gallerist Marilena Bonomo in the early 70s and kept going back.

Sol was a private man. He avoided the spotlight. He believed the public should look at art, not at artists. He bought other people’s work constantly. He mentored freely and wrote catalogue essays for people nobody had heard of.

His wife Carol said he was looking for “an Italian girl with a driver’s licence” who liked taking care of him. He was an impatient tourist who remembered everything. He could absorb an entire fresco cycle in the time it took other people to read the information panel.

The frescoes in Italy changed his work completely. Although his ideas were set by 1967 they had an effect on his visual language. Colour arrived. Washes, arcs, fans, cascading triangles. The wall drawings stopped looking like engineering diagrams and started looking like something Giotto might have sketched in his sleep.

He moved back to the States in the late 80s, settled in a small Connecticut town, and kept working until the end. When he died, the local restaurant had his prints on the walls. Nobody made a fuss about it. That’s how he wanted it.

Key works

Standing Open Structure, Black (1964) — A painted black wooden rectangle, 96 inches tall. Human-sized. Skeletal. The prototype for everything. When a museum later asked if they could just rebuild it elsewhere (since he was a conceptualist…), he says no: “Would you repaint a Mondrian?”

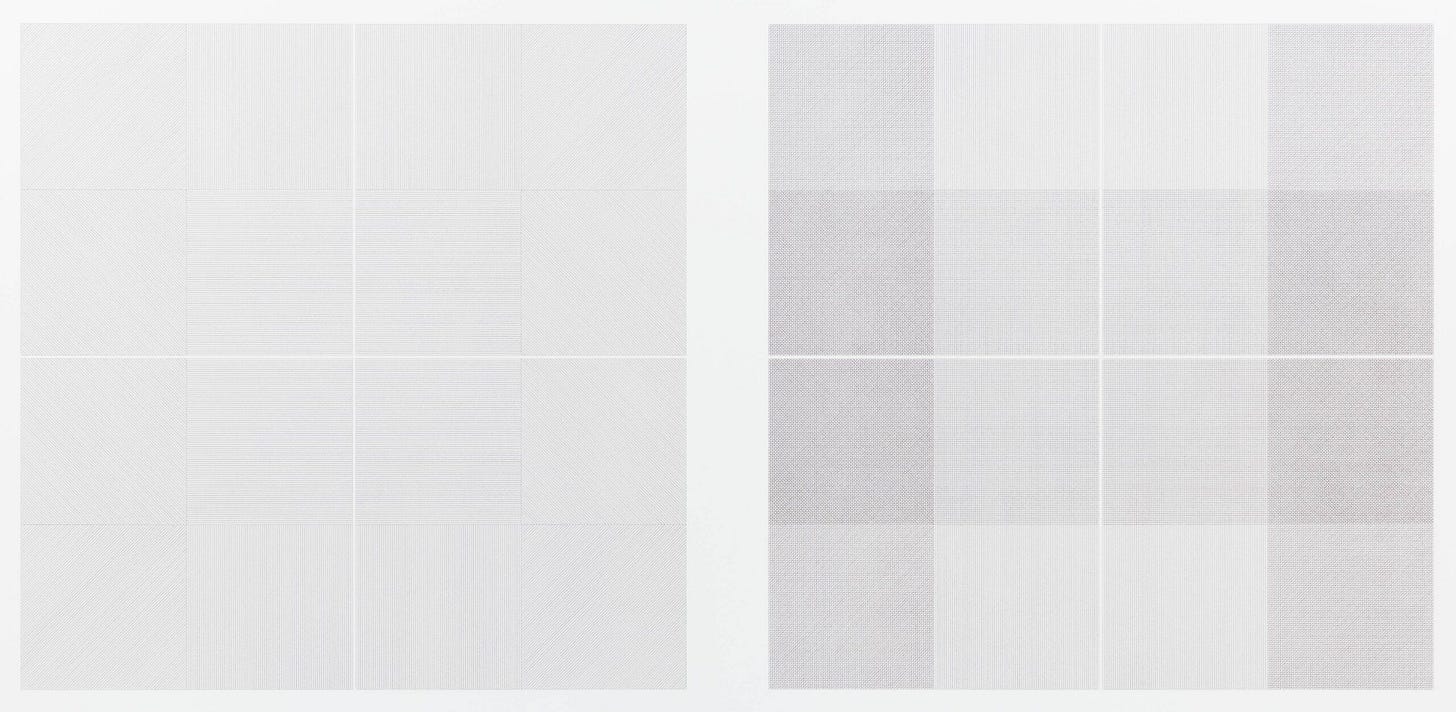

Serial Project No. 1 (ABCD) (1966) — Nine pieces in four groups. Open and closed forms. Every variation in two and three dimensions, using the fewest measurements. This is art that looks like architecture for a civilisation that thinks in grids.

Wall Drawing #1 (1968) — The beginning. Pencil on wall. Temporary. The instructions survive. The drawing doesn’t. He did this 1,200 more times.

Paragraphs on Conceptual Art (1967) — Arguably his most influential written work. Gave the movement its name and operating system. “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” “Banal ideas cannot be rescued by beautiful execution.” “It is difficult to bungle a good idea.”

Wall Drawing #46 (1970) — Made days after Eva Hesse died. The first freehand wall drawing. The system collapses on purpose. Grief as method.

Incomplete Open Cubes (1974) — 122 ways to not make a cube. Every arrangement of edges has something missing. You can’t look at them without mentally trying to complete the shape. It’s a work about absence. About the thing that isn’t there, being the thing you can’t stop seeing.

Wall Drawing #439 (1985) — Made in Italy. Colour ink washes in cascading triangles. The conceptualist discovers what Giotto knew: you can create depth on a flat plane with nothing but colour and conviction.

The Letter to Eva Hesse (1965) — Not technically an artwork. But 100% Art lore. A letter to a friend who was paralysed by self-doubt. “Do more. More nonsensical, more crazy, more machines, more breasts, penises, cunts, whatever — make them abound with nonsense.” “You belong in the most secret part of you. Don’t worry about cool, make your own uncool. Make your own, your own world.” This letter circulates today like a prayer for blocked artists. It reveals the thing the conceptual framework sometimes hid: LeWitt believed in feeling first, systems second.

tl;dr

Systems art. You can build a practice around instructions. The artist’s role can be designing the system, not executing it. The gap between instruction and execution, between what we intend and what actually happens, is where the art lives.

Dig for gold. LeWitt returned to the same questions for forty years and found them inexhaustible. He didn’t chase trends. He didn’t rebrand for each decade. He went deeper into one set of ideas until the work became richer than anyone thought possible.

No ego. By removing his ego, he created a practice that outlives him. The MASS MoCA retrospective runs until 2033, fresh hands drawing his instructions on new walls, decades after his death. The system persists. The artist is gone, and the art continues.

Notes on… is a new series where I share the artists, books, and ideas that fuel my practice. If there’s someone or something you want me to cover, reply to this email.

I’ll probably be releasing it on Substack only. I feel like two emails in your inbox every week might be a bit too aggressive, but let me know what you think here:

Love you loads

- R x